Regenerative design is a hot topic at LHB these days. A term borrowed from agriculture, regenerative describes a system that gives back—like a field planted with crops that not only yield food, but also store water, add nitrogen to the soil, and provide shade for wildlife.

LHB designers are interested in how regenerative concepts can be applied to structures and spaces. The goal is to create multifaceted and beneficial results from limited resources.

But is regenerative just another word for sustainable? No, it’s a significant leap forward, says LHB CEO Rick Carter. That’s why LHB’s staff is investing time and effort in understanding the concept. Here, Carter talks about regenerative design and why architects and engineers should embrace it.

When did LHB start to focus on regenerative design?

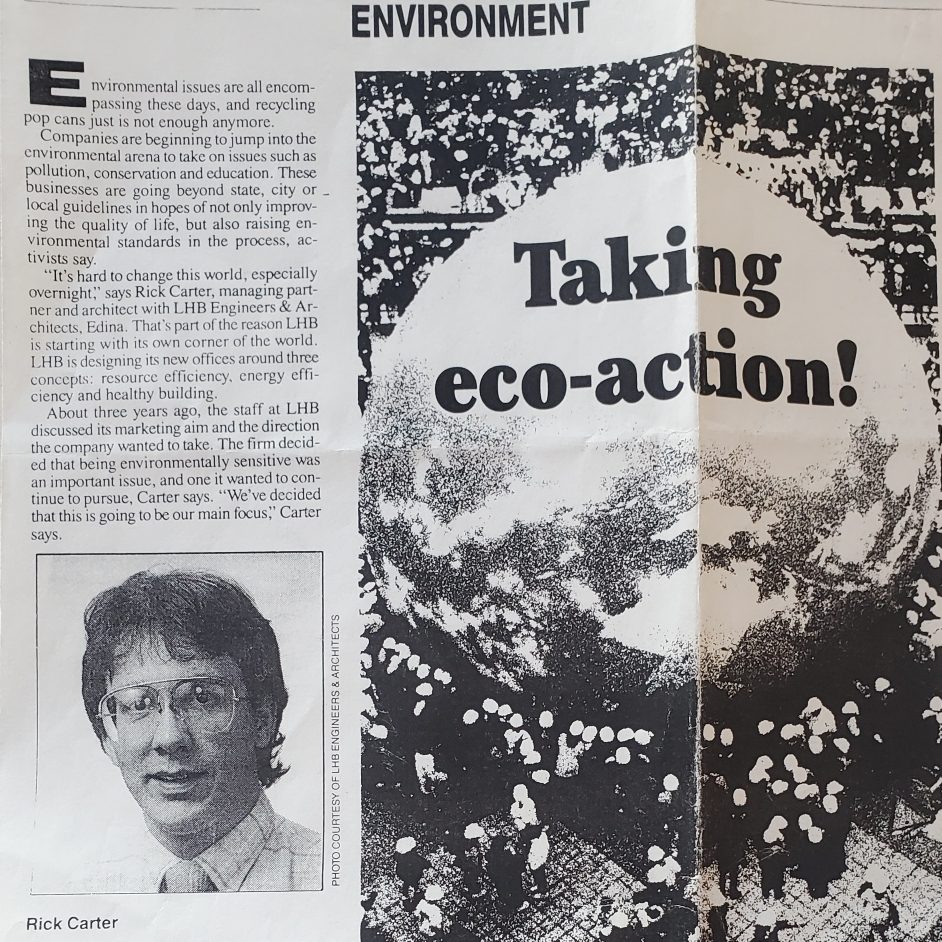

Rick Carter: The conversation we’re having today about regenerative design essentially began three decades ago. LHB was founded in Duluth in 1966, and in 1988 we opened an office in the Twin Cities. We found a space in Edina and had a ton of work at first, but within a few years, it had tailed off. We realized we needed a differentiator, something that could set us apart from the competition. We gathered everyone together and eventually settled on something we called “healthy building” design.

What was “healthy” about your approach?

Rick Carter: The concept revolved around energy efficiency, occupant health, and resource efficiency. We all agreed these things were important in architecture and engineering, and we were going to learn more about them and how to integrate them into projects. Nobody was really talking about climate change or greenhouse gases as they related to architecture. We used to say it was “healthy for the planet, you and your pocketbook”.

Who were your clients?

Rick Carter: We got some grants from a state agency to do studies on building energy and resource efficiency. We began to learn more about “sick building syndrome” and got hired to build a home for a client who had multiple chemical sensitivities and was concerned that her home and workplace were making her ill. A small tech company also hired us to design a “healthy workplace” for them. And we began to explore the idea of building less and repurposing structures and reusing materials—a form of recycling, if you will. It quickly became clear that this was a real vacuum in our industry.

Reuse became part of the business.

Rick Carter: In the early 1990s, a Minneapolis nonprofit called the Green Institute hired us to retrofit an old storefront on Lake Street into an outlet for salvaged building materials. It really challenged us to think through everything: What could be reused, repurposed, recycled, salvaged?

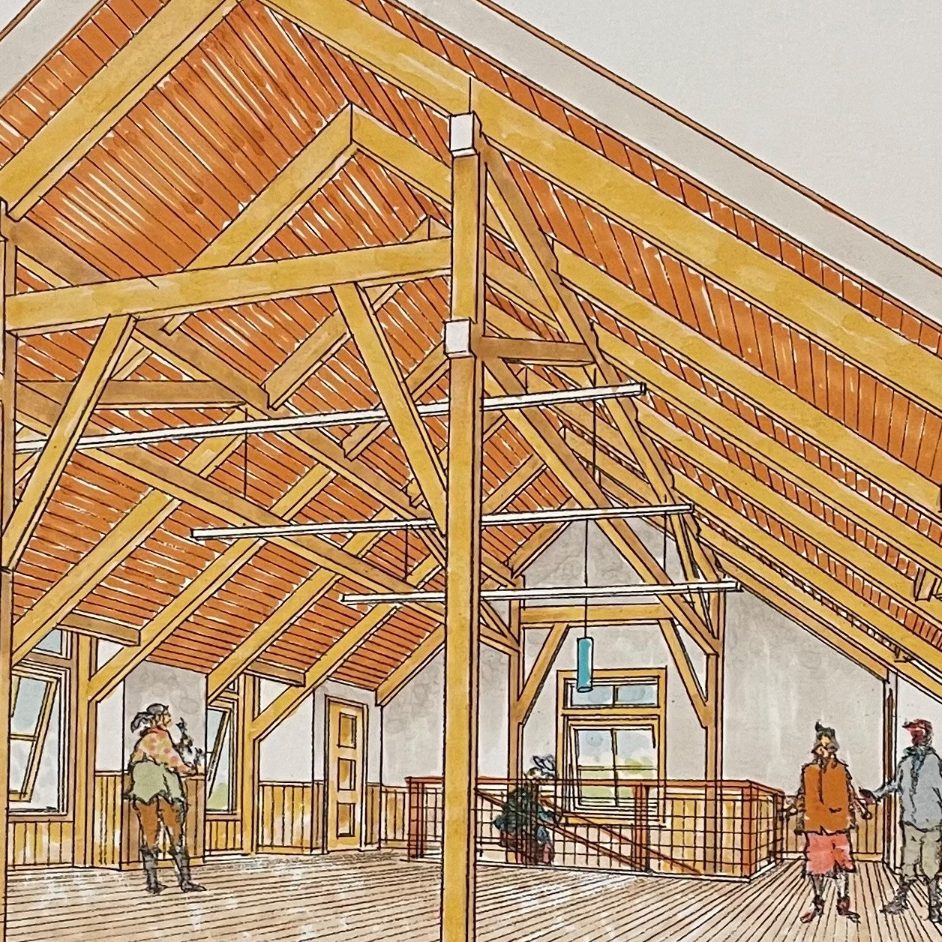

That same client hired us again in the mid-1990s to design the Phillips Eco-Enterprise Center, where we pushed the boundaries of typical design even further. We shrank the parking lots and filled the extra space with prairie plants; we used salvaged steel joists in the warehouse; and we designed geothermal pumps and solar panels to reduce energy costs. We had to persuade city inspectors that the solutions we were proposing could really work—and we succeeded.

Measuring costs and efficiencies was important, right?

Rick Carter: Yes. In the mid-2000s, I went to a talk by Ed Mazria, an architect who was really out front on sustainability, resiliency, and greenhouse gas emissions. He talked about comparing energy consumption in buildings by measuring kBTUs per square foot—just like you’d compare fuel consumption using miles per gallon in cars. I went back to the office and said, “We’re going to calculate the kBTUs for every building we design.” We made a giant spreadsheet and started measuring everything. It was a little crazy, but now it’s kind of expected.

You called it “Performance Metrics.”

Rick Carter: It started with energy, but evolved to include waste, stormwater, materials usage…and eventually greenhouse gas emissions. In 2010, we created the Regional Indicators Initiative to help cities track data on all these categories, and we developed a tool called Thrive for internal use in 2018, allowing us to evaluate projects based on their climate and community impact, among other things.

When did LHB embrace regenerative design?

Rick Carter: The real shift in our thinking came when we realized it wasn’t enough to just “do less bad.” Reducing consumption is great, but what if we set our sights on creating more resources altogether? What if our buildings produced more power than they needed, putting power back into the grid? What if one of our designs helped clean water or improve air quality for an entire region? In 2016, our Integrative Design Team, which focuses on buildings and sites, committed itself to creating “regenerative communities.”

What’s a regenerative community?

Rick Carter: It’s a community that produces more resources than it uses—adding energy to the grid, for example, or providing jobs in an area that needs them. We’re currently involved in The Heights in St. Paul, which has the potential to be the first truly regenerative community in the world. It also draws on our cross-sector knowledge of energy, land-use planning, housing, commercial architecture, infrastructure, and more.

What does regenerative design mean at LHB?

Rick Carter: We want to be at the forefront of design as the world transitions to a clean energy economy. Practicing regenerative design is an important slice of that. We know that the way architects have traditionally designed structures—always using new materials, relying on fossil fuels for energy, often ignoring environmental and community impacts—has to change. If our profession can design structures and spaces that go beyond sustainability and generate more resources than they use, regenerative design will be a win for the entire planet.