The City of Hopkins, just west of Minneapolis, is often called a suburb.

But unlike the leafy, lake-filled enclaves that surround it, Hopkins is quite urban and diverse. Nearly two-thirds of its 20,000 residents live in apartments, rather than single-family homes, and large chunks of the city — four square miles in size — are zoned for industry and manufacturing.

Recently, city leaders began to engage the community in conversations about how the city’s landscape and future will be reshaped by climate change. How will climate change affect the city’s industries? How can residents prepare for rising temperatures, increased storm intensity, and changing habitats in the years ahead?

In 2021, Hopkins special projects and initiatives manager PeggySue Imihy Bean approached LHB and Local Climate Solutions, a consultancy, about developing a tool that might help direct this discussion. She’d found a map that highlighted high-heat patterns in certain city neighborhoods and wondered how climate change would intensify the impacts on these areas.

LHB’s Lydia Major and Jess Vetrano, members of our landscape architecture and planning studio, teamed with Abby Finis, founder of Local Climate Solutions, to dig into the data and interview area residents. The result was the Hopkins Heat Vulnerability Study that helps decision-makers and residents alike explore the impacts of heat. The pair recently joined PeggySue to talk about how the story map was created.

Why did Hopkins dig into the topic of heat vulnerability?

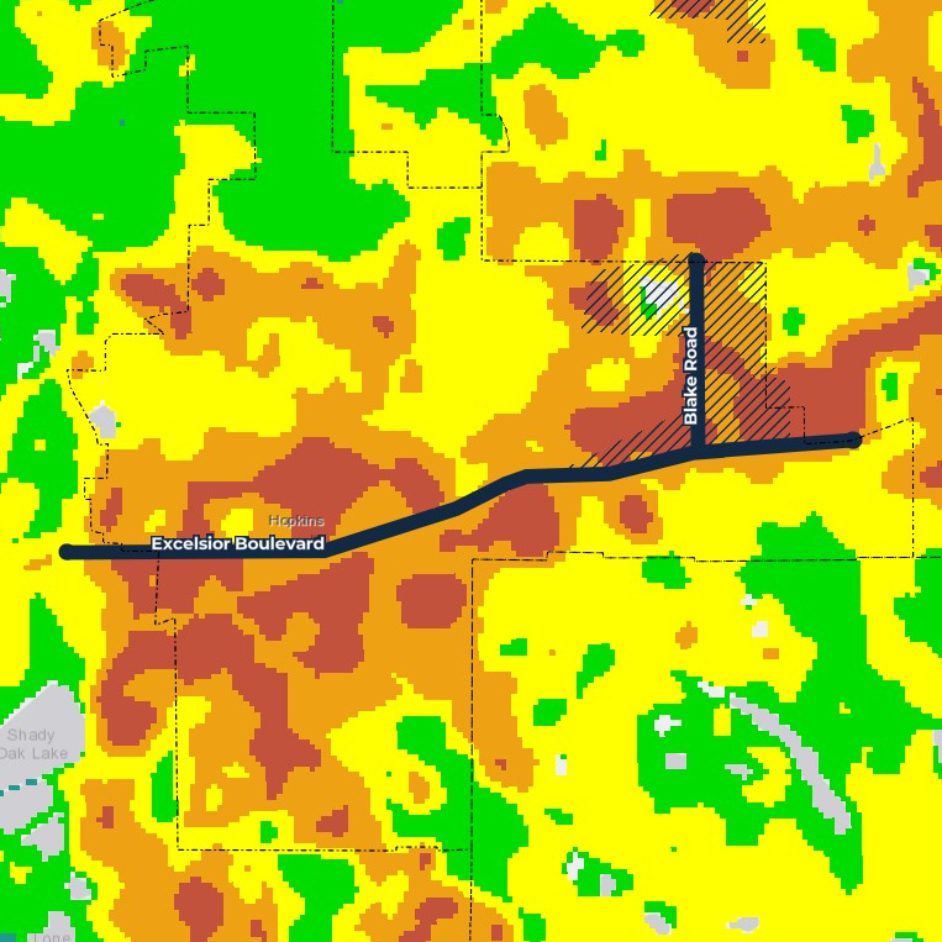

PeggySue: Hopkins has begun to focus more on sustainability and racial equity in recent years, and we’ve looked for low-cost ways to engage our community in conversations about these topics. I came across a Met Council map that showed land surface temperatures on the hottest days in Minnesota and noticed that our community was mostly orange and red. On the map, it resembled a big-city downtown — with lots of asphalt, black roofs, and intense heat during the summer.

The heat is most intense, though, in corridors where Hopkins has a lot of multifamily housing. We know that 65 percent of all our residents live in rental housing, and 90 percent of people of color in the city are renters. These places are often home to low-income households, people of color, and new arrivals to the United States.

Are you saying heat has the most impact on residents who have the fewest resources?

PeggySue: Yes, but I don’t think it’s intentional. It’s a result of the kind of urban development we used to do, where big apartment buildings are surrounded by big parking lots. There’s lots of surface area that absorbs heat—and not much shade. Anyway, we wanted to know: How can we fix this to benefit everyone, including residents and property owners?

What kind of data collection and interviews did you do?

Lydia: We started with analysis, studying similar communities that are dealing with heat. We looked at existing conditions, used GIS to do some mapping, and looked closely at tree cover and impervious surfaces. We had a number of community events. Abby and PeggySue went to a very hot National Night Out (it was 99 degrees!), and we had a big community event where there was food and a bike exchange and great turnout. We asked residents how they deal with heat.

What did residents say?

Abby: One thing that stood out is almost everybody seeks air conditioning if it’s hot. That’s our coping mechanism. All the single-family homes in the area had central air. But apartment buildings usually have just a window unit in one room, so the rest of their unit is hot. Some folks said they had to give up paying for other things in summer to be able to afford air conditioning.

Why didn’t people go outdoors?

Abby: Going outdoors to cool off wasn’t really an option anyone considered. Generally speaking, urban design in America has created outdoor spaces that are undesirable. You don’t want to sit out in an asphalt parking lot or walk along a treeless street. We’ve pushed people inside, and our urban design has made outdoor spaces even hotter.

What can property owners do to mitigate heat?

Lydia: The number one thing they should do is plant trees. Trees have multitudinous benefits. They provide shade, absorb heat, and are relatively cost-effective. Owners can also reduce paving, change roof surfaces, add shade structures — these strategies can have a big impact.

What role can concerned neighbors play in reducing heat vulnerability?

Abby: Socially isolated and lower-income tend to be the most vulnerable to heat events. Fostering social cohesion among residents and neighbors is important. We should be checking in on residents who don’t have anybody else that they can reach out to.

What can the city do to reduce heat dangers?

PeggySue: First, the city can provide education to residents and property owners. That’s why we made a story map. A lot of paper plans get presented to the city council, but they’re not community resources. And we really wanted the story map to be accessible.

Second, the city can provide funding. We just rolled out Hopkins Climate Solutions Fund to incentivize people to plant more trees, do less paving, paint their roofs white, and more. We can encourage investment in sustainable improvements like solar gardens. Many people are interested in the cost-saving aspects of these changes. It’s an added bonus beyond the opportunity to reduce heat and other impacts of climate change. ∎