Attending conferences like the U.S. Green Building Council’s Greenbuild is one of my favorite ways to stay inspired and connected to a broader design discourse. Here are just a few things I learned when I traveled to Boston for this conference in November 2017.

1. How to heat a building with eleven hair dryers

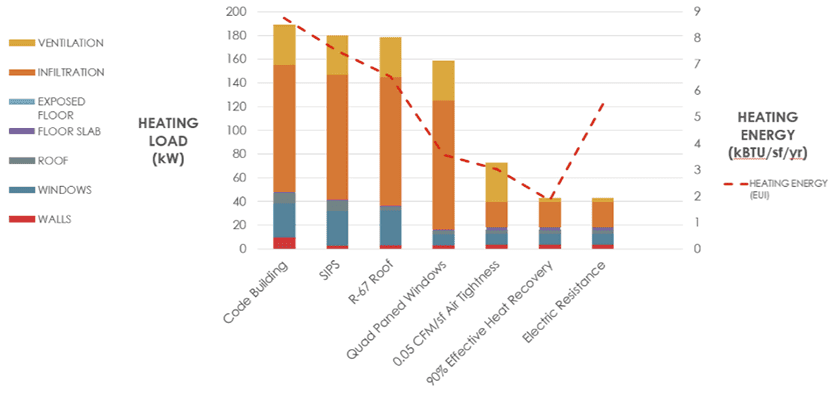

They don’t really heat it with hair dryers, but the heating load at Rocky Mountain Institute’s Innovation Center in snowy Colorado is small enough that they could. By using energy modeling to track the impact of design decisions on the building’s loads, the design team was able to eliminate air conditioning and dramatically reduce the size of the building’s heating system. Focusing on passive strategies (including structural insulated panels, quad-pane windows, thermal mass, and phase change materials), the project team reduced the heating loads enough that they could be met primarily by clothing choices and desk chairs with individual thermal control, with electric resistance radiant heating available for the coldest days. With the money saved in mechanical system first costs offsetting the extra cost of these passive strategies, the Innovation Center has a payback period of only 3.9 years, and produces 20% more energy than it consumes.

2. How to track comfort and wellness-related outcomes

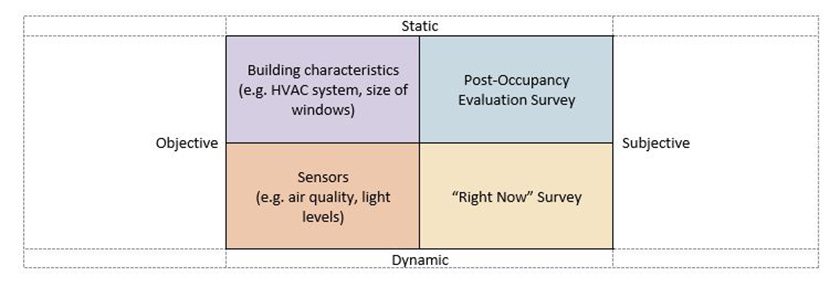

With design for human wellness bursting onto the international stage with the release of the WELL Building Standard in 2014, many of this year’s Greenbuild sessions highlighted metrics, methods, and technologies for tracking comfort and wellness-related outcomes in the buildings we design. After hearing about various uses of physical measurements, sensors, and occupant surveys, it was helpful for me when a group of panelists presented a framework for categorizing these evaluative tools (see image below). With one axis representing a scale from objective to subjective and the other axis ranging from static to dynamic, this framework inspires me to think more broadly about potential post-occupancy services for LHB projects.

There are pros and cons to using tools from each of the four quadrants in terms of their practicality, usefulness, and relative cost. However, to use post-occupancy data to inform our design work requires engagement across these categories as we seek to understand how people feel in the space relative to the physical characteristics that we have control over.

3. How to listen

For the first ten minutes of a “Design Process Hackathon” facilitated by Tristan Roberts, Andrea Love, and Jennifer Preston we were challenged to:

- Ask a stranger an open-ended question – “Tell me why you’re here”

- Focus entirely on listening to his or her response, and then

- Ask another open-ended question – “Tell me more about…”

The neat thing about the prompt “Tell me why you’re here” is that it can provide insight into a person’s current mental space, where “here” can range from “in this specific chair” to “on this earth.” One person might describe how the current political discourse has colored her experience of this year’s Greenbuild, while another might dive straight into a challenge he’s encountering on a specific project.

Though asking the open-ended question was easy enough (especially when the prompt was provided for us), the next two steps were harder than they sound. As soon as my partner said something that I could relate to, I struggled to keep listening – rather than formulating a response in my head – and struggled even more to ask a second open-ended question rather than jumping in with “the same thing happened to me, have you tried…”. As creatures adverse to awkward pauses, we tend to listen with half an ear while busily planning out the next thing we are going to say. And as problem-solvers, we tend to contribute ideas before fully understanding the problem.

Architects are great problem-solvers. But to problem-solve in a way that’s meaningful to our clients, we need to first be great listeners.