Attending conferences like the U.S. Green Building Council’s Greenbuild is one of my favorite ways to stay inspired and connected to a broader design discourse. Here are just a few things I learned when I traveled to Los Angeles for this conference in October 2016.

1. How to make the business case for doubling an office’s ventilation rate

3/30/300. This is how much a typical office might spend annually on energy, rent, and labor: $3 per square foot on energy, $30 per square foot on rent, and $300 per square foot on labor. This relationship makes it clear that design strategies that improve employee productivity have a great potential for meaningful payback.

In an exploration of the impact of indoor environment quality on cognitive functions, the COGfx Study found that an increase in ventilation rates from 20 to 40 cubic feet per minute of outdoor air resulted in an increase in employee decision-making performance that equates to $6,500 of increased productivity each year. Since doubling the ventilation rate costs less than $40 per person annually across all climate zones studied (and costs much less when energy-efficient technologies are used), the value of this increased productivity is more than 150 times the extra energy costs.

2. How to achieve thermal delight

Imagine soaking in an outdoor hot tub during a winter storm, or moving from a scorching parking lot into an air-conditioned grocery store. Humans derive pleasure from thermal variation, whether spatial (different body parts experiencing different temperatures) or temporal (moving from one thermal condition into another). However, this concept of alliesthesia – the notion that sensory pleasure is dependent on one’s internal state – is not typically incorporated into the design of the built environment, which more commonly aims to maintain a standardized temperature range regardless of the outdoor conditions or intended use of the space.

So how can we incorporate thermal delight into our building designs? Here are a few ideas:

- Engage in thermal programming. What conditions will best support the people using each space? Consider level of activity, clothing, and length of time spent in each space.

- Design the building mass and envelope to passively provide the thermal conditions needed in each space (or vice versa), and be thoughtful about the placement of spaces that aren’t continuously occupied.

- Diagram the thermal pathways that lead to and through the building. Imagine each of the conditions a building occupant will experience throughout their day. Don’t forget to consider how these pathways will change with the seasons.

From “Finding Thermal Nirvana: Creativity in Thermal Design” by Gail Brager, Claire Maxfield, and Shruti Kasarekar

3. Why the importance of thigmotaxis should never be underestimated when designing public space

Wiktionary defines thigmotaxis as “the movement of an organism either towards or away from the stimulus of physical contact”. The speaker at this session, Ann Sussman, put it a little more clearly: “wall-hugging”. People like edges. Whether in restaurants, airports, or public plazas, we prefer to occupy the spaces near walls rather than in the open center. This makes sense evolutionarily; sitting with your back to the wall, no one can sneak up on you, and you have a clear view of any threat that may approach. It also fits in with the biophilic patterns of Prospect and Refuge.

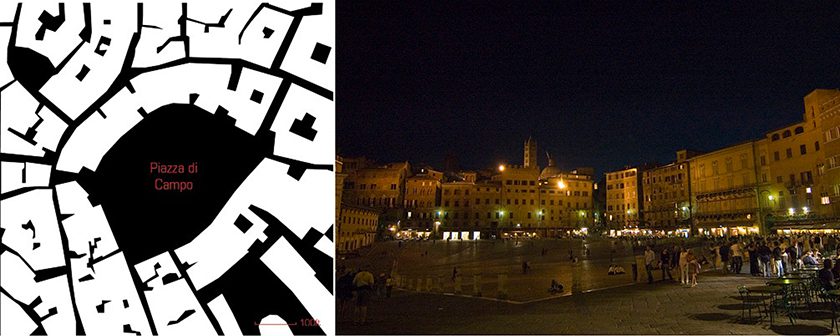

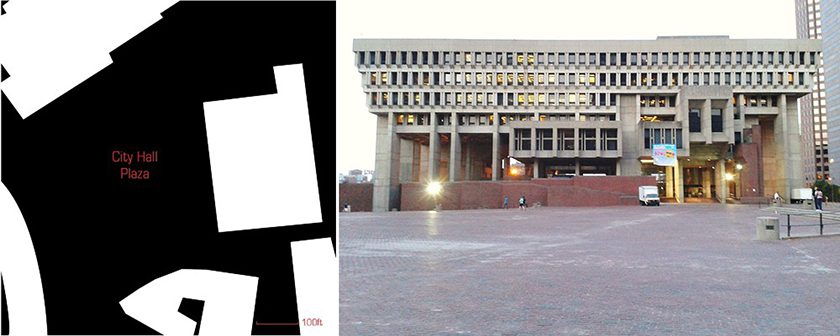

This affinity is apparent in the success of our public spaces, as shown in the contrasting examples below. While the Piazza di Campo in Siena is full of life (especially around its edges), the large scale and lack of defined edges in the City Hall Plaza in Boston does not invite human habitation.

If you design the right kind of edge, our brains will stick close to it.

From “Cognitive Architecture: Neuroscience Informing Green Design” by Ann Sussman and Neal Payton